I buy my books at this little used bookstore tucked into the corner of a particularly dusty strip-mall. Outside the store, they have a pair of shelves where the books are only one dollar. I’ve hit gold on the dollar shelf several times. I got a brilliant novel called The Siege of Krishnapur there and a collection of Elizabeth Bishop’s letters and Two Years Before the Mast.

But the catch here is that you get some beaten-up books. You get them with the binding glue gone stiff, yellow and chipping. And, very often, you get books that have been annotated — little notes in the margins, left by previous readers. It’s distracting at first. But then you train yourself to say to hell with it. You can read around the annotations.

I’ve probably read about thirty of these marked-up books. And as often as not, they’re only annotated in the beginning. Readers tend to abandon either the text or their pens after about thirty pages. And the margin notes are rarely helpful because margin notes are only notes to yourself, right? About your own interpretation of the text?

This was supposed to be a piece about whether or not we should write in our books. At least that’s the piece that Esquire rejected. And I certainly wouldn’t admit it to Esquire, but I’ll admit here that I frequently write in my books. Anything I’m reading for the third time, anything I’m studying. I’m scribbling all over the place. Writing in your books slows you down, makes you get into the text. And sometimes — particularly with the head-inflating crowd — you just have to call the author on his/her shit. I mean, have you ever tried to read Nietzsche without calling him a douchebag in the margins?

As a quick word from our sponsor (you) — do we write in the margins? I’ll put a poll here.

True, there are arguments against writing in the margins: the basic principles of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder or pristine bibliophilia. A graffitied book is a messy book, so goes the logic. It’s really a question of morality. And you might believe that scribbling takes you out of the text. On a surface level, I agree with that. I once annotated two Taylor Jenkins Reid novels and it a felt a bit like dissecting a cancerous frog. The slowness of it. She’s a decent writer but you have to move quick.1

This was also going to be a piece pondering whether I should be writing more in my books. But I think it’s probably a question of effectiveness vs. morality. Maybe it’s a sin for us to write in our books; but maybe it also makes us better readers. I’m not going to tell you what you should do. If you want to write in your books, well then, do so. If you want to doodle dicks or madonnas into the margins, that’s none of my business. But should I do it? And if writing in your books makes you a better reader, should I being doing it more?

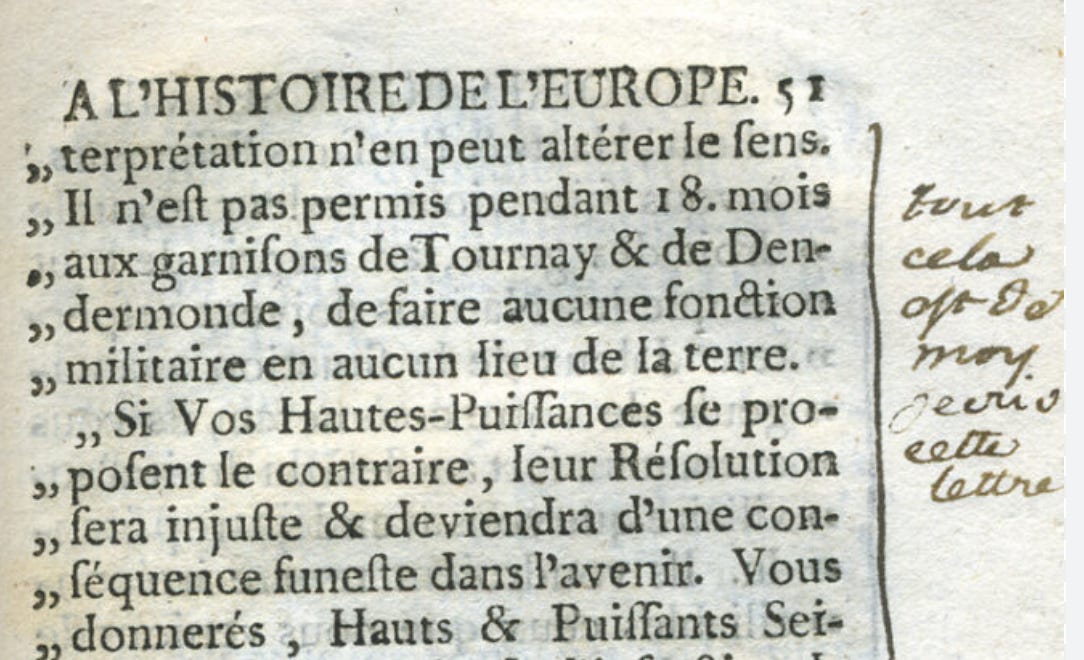

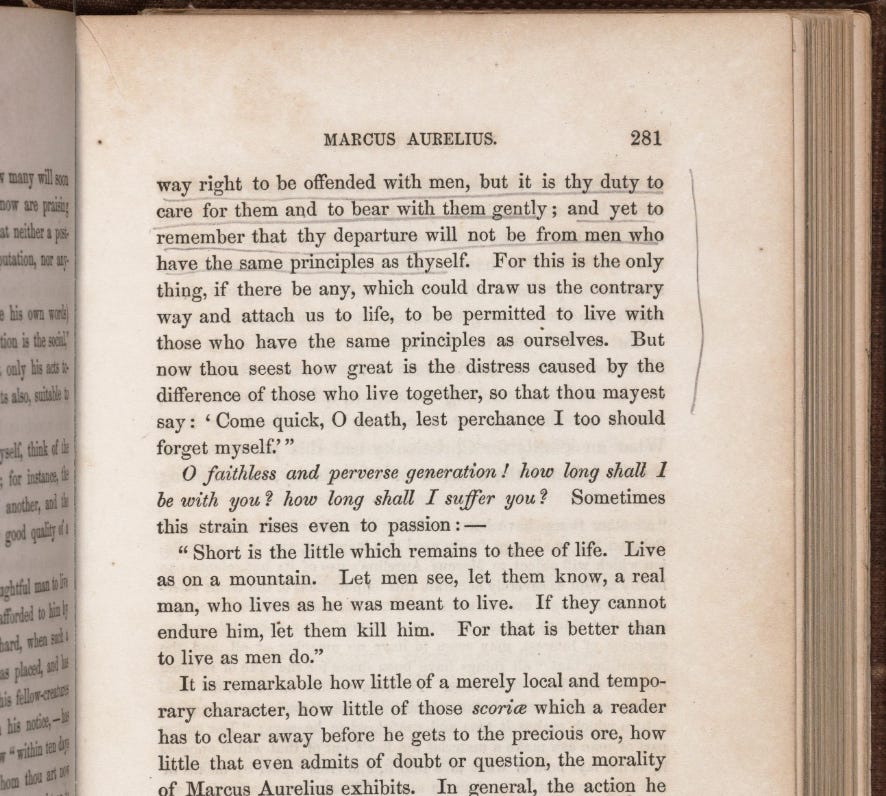

About two years ago, I was scribbling all over the margins of Moby Dick and I remembered a Melville scholar I once had drinks with who told me that Herman Melville himself was a notorious margin writer. I looked it up and turns out it’s true — there’s a whole website called Melville’s Marginalia with digitalized versions of Herman Melville’s marked-up books. Here’s his annotated copy of Marcus Aurelius.

And here’s Melville’s marked-up copy of Milton’s poems with the note: “from Jesus to Shakespeare.”

Of course it’s not just Melville. Lots of writers were margin writers. Voltaire supposedly wrote in nearly all his books. Unfortunately, his entire library is in Russia. Catherine the Great bought it after his death.

But we have Mark Twain’s stuff, and that’s arguably better. The dude was hilarious and brutal in the margins. Some of his notes were digitized by the New York Times. In one line, he accuses the writer of stealing an image and then, subsequently writes “ditto” under the next bits. (also, ditto was apparently part of Mark Twain’s vocabulary … weird)

Twain would frequently accuse authors of theft, like he did here with the notation, “another theft.”

I mean, when viewed through this lense, writing in your books is cool, right? These are the footsteps of our greatest literary figures. You feel a bit like, well now how can it be bad to write in my books if Voltaire did it? You feel as though you’re being peer-pressured through the centuries.

And, on that note, I suppose I should go back to the beginning here. I suggested that it’s unpleasant to get the marked-up books from the dollar rack. But then again, it’s not such a bummer when you get a marked-up book, it’s even a bit nice. It kind of feels like you’re sharing something with some stranger, some viscerally human human-being whom — just like you — went looking for answers from Schopenhauer or Carl Jung. And there’s that feeling that this book was thoroughly appreciated. Like, it lived a life before it fell into your hands. And that’s nice too.

You ever try to close-read a page-turner? There’s nothing under there. But I wanted to see what made everybody obsessed with Daisy Jones & The Six and Malibu Rising. Two big tricks I learned: heavy-handed foreshadowing and cliff-hangers

I especially liked the last paragraph. I do not write in my books, but maybe I should. In college, I wrote in my texts. I do know that when I pick up a used book and find the writings of some unknown reader, I am a bit excited each time. Whether it makes sense to me or not, it feels like an intimate moment between readers.

I wrote all over my books in college but find them too sacred to write in now. They were tools then, objects of love now. That said, for me finding writings in books forms a connection to whoever owned and read them before, like a book club over time and space. Including my college books. How cool is it to connect with a younger, earnestly passionate version of myself? However, NOT in library books. That's the worst. Evil. Just no.